The Grand Budapest Hotel

/[to Mme. Celine’s corpse] You're looking so well, darling, you really are... they’ve done a marvelous job. I don’t know what sort of cream they’ve put on you down at the morgue, but... I want some.

~ M. Gustave

quick fox: A+ | Gold

winding dragon

One of my favorite paintings is the Surrealist painter Magritte’s Son of Man. It’s deceptively complex—a green apple dangling in front of a man in a gray suit and bowler hat. But it’s layered underneath obscure meanings that defy a single, direct interpretation. Son of Man could be about social identity (the face hiding behind the apple), biblical allegory (the apple being Eden’s forbidden fruit), or even political disconnection (the unknown face).

And following in a similar abstract fashion, is Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014).

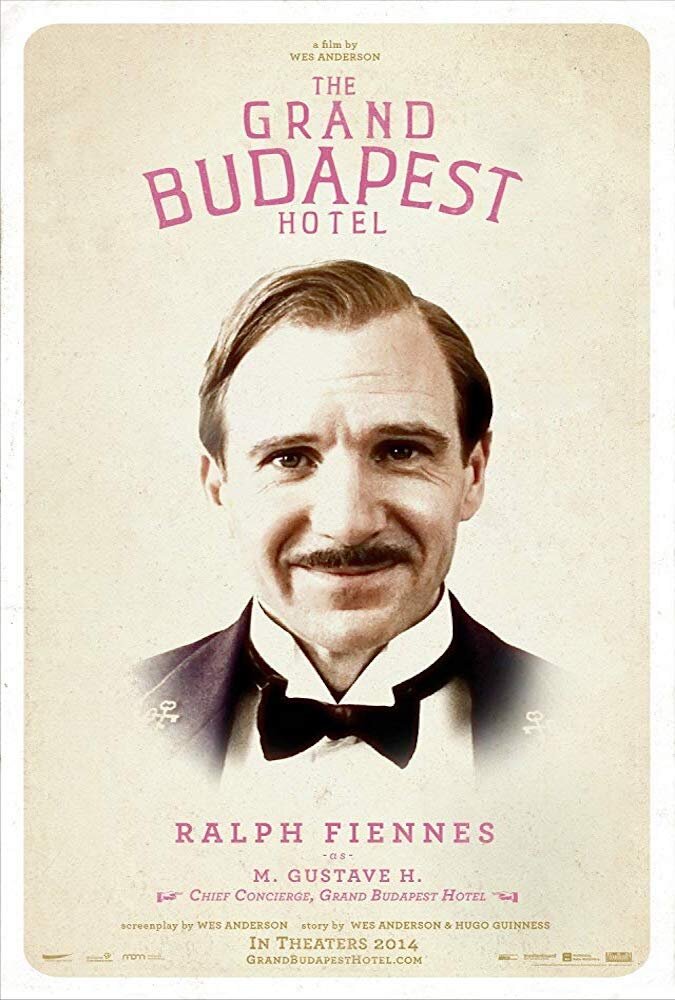

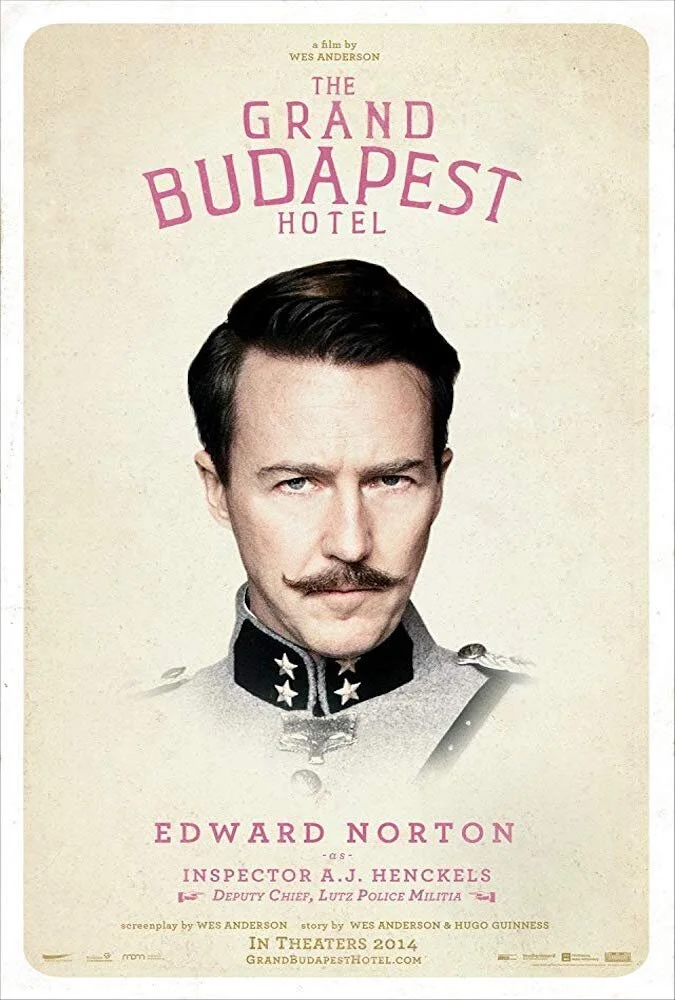

Explaining what it’s about is a little confusing. It’s a frame narrative, told through a book about an author’s (Jude Law) oral recount about a personal narrative he once heard. It centers on Monsieur Gustave (Ralph Fiennes), the devoted concierge of the Grand Budapest during the early 1930s, who is a relic of a dying era when the aristocracy would take extended vacations in elaborate hotels. Gustave’s struggle to uphold an outdated age is metaphorically manifests itself when an elderly guest, Madame Céline (Tilda Swinton), is murdered and Gustave is blamed. Following Gustave every step of the way is his dutiful lobby boy, Zero Moustafa (Tony Revolori), and together they become fugitives, trying to escape investigative forces much like Gustave tries to escape being another victim of the dying age.

But what does it all mean?

Well…I can’t tell you that.

Wes Anderson is the sort of director who loves to subvert every convention in not only technical elements but also conceptual expectations of clearly outlined interpretation. Many of Wes Anderson’s characters are like the apple-veiled human in Magritte’s painting—visible but unknown.

Gustave is no exception. Though the majority of the movie is spent following the man—as if the audience is acting as a collective “lobby boy”—it’s almost impossible to say who Monsieur Gustave really is. I could list what he does. I could describe his clothes. I could even analyze his speech patterns and language. But it would do little to accurately describe why Gustave does anything, and neither does he offer explanation.

Instead, The Grand Budapest Hotel is like a moving, breathing surrealist painting, forcing the audience to draw a conclusion of their own making. And it does so by crafting a visual aesthetic—from the vivid colors to the elaborate set design to the indulgent, precise cinematography—that I found to be one of the most enthralling spectacles I’ve ever seen.

To ask somebody what the meaning of The Grand Budapest Hotel seems counterproductive because it’s such a unique, individual experience that I doubt any two people would completely agree on the same interpretation. For myself, the movie is—in a broad sense—a reflection on legacy, and making a statement on how life is only worth living if you leave behind a story worth telling.

And for The Grand Budapest Hotel, the story is worth every minute.