Isle of Dogs

/I’m not doing this because you commanded me to. I’m doing it because I feel sorry for you.

[Fetches stick and brings it back to the Little Pilot]~ Chief

quick fox: A- | Silver

Isle of Dogs is deceptively simple. The gravity of the political situation and the outstanding technical effects can overshadow that the heart and soul of the film is a boy’s love for his pet and a dog’s love for his master. And that’s beautiful. Isle of Dogs is not meant to appeal to the mass public — Anderson’s idiosyncratic style creates a very offbeat humor and the highly conceptual nature of the film makes it difficult to feel confident that you’ve understood the overall purpose of the feature. But I think it’s a dazzling production, with a incredible display of how far stop-motion has come since the days of Rankin-Bass Christmas specials (the style was an inspiration for this film, according to Anderson). Isle of Dogs pushes the audience to consider their place in the world and what they contribute to it, on both large and small levels. It’s definitely a film I will be returning to again and again.

winding dragon

Sometimes when I watch a Wes Anderson film I feel like I understand Cameron a little better, standing before Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. In Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Cameron fixates on the dots compromising the pointillism masterpiece rather than the whole painting, with the camera cutting between Cameron’s eyes and the dots of paint. Anderson’s production is likewise mystifying, enchanting, and speaks to my own personal standards of beauty — though perhaps I can’t explain why. In Anderson’s latest film, Isle of Dogs, the point or moment that most captures my attention is a dog being hugged by a boy, surrounded by a literal mountain of trash.

But let me explain the story first and maybe it’ll make more sense.

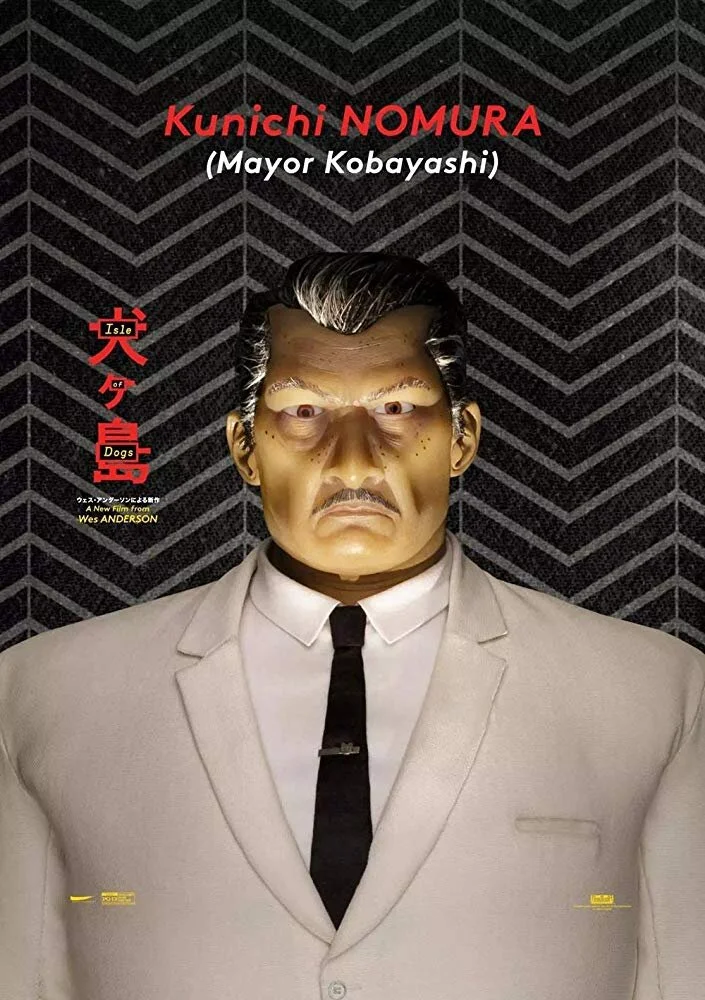

In a futuristic, dystopic Japan, dogs have contracted snout fever — a disease which causes uncontrollable sneezing, bloodshot eyes, and hyper aggression — leading to public outcry against man’s best friend. (To be fair, the dogs do look like they’ve had every loose strand of their fur Velcroed back onto them.) The power-hungry mayor of Megasaki, Kenji Kobayoshi (Kunichi Nombra), exiles all dogs (beginning with his personal bodyguard dog Spots) to a nearby dumping grounds aptly called “Trash Island.” Six months later, all dogs — domestic and feral alike — scrounge for shriveled apple cores, fish bones, and moldy banana peels. In the midst of this canine Lord of the Fleas, a pack of 5 dogs struggle to fend off their inevitable demise: Chief (Bryan Cranston), Rex (Edward Norton), King (Bob Balaban), Duke (Jeff Goldblum), and Boss (Bill Murray).

The star of our canine band is Chief, a black-haired stray who, despite his admonitions to the contrary, is the leader of his other domesticated companions. Cold, rebellious, but secretly a “good boy,” Chief’s attempts to harden his friend’s hearts against Trash Island’s brutal dog-Darwinism go astray when The Little Pilot crash-lands on the godforsaken island. The 12-year-old Atari Kobayashi (still bleeding from a lead pipe of the airplane embedded in his head) tries to explain to these dogs that he is the orphaned nephew and miserable ward of Mayor Kobayashi. He is here to rescue Spots, the Kobayashi guard dog. Unfortunately, the dogs only speak in barks (translated to English for the convenience of many, as the opening titles explain) and the boy only speaks Japanese (which is not translated into English).

Meanwhile, back in the fictional city of Megasaki (in Japanese, this name is nonsensical when translated to English), Mayor Kobayashi tried to spin public opinion in his favor — it’s really not good for his image that his nephew defied the law to rescue the family’s disease-ridden pet. But by blaming the dogs for kidnapping his nephew (propaganda that seems dubious at best), and publicly broadcasting drone surveillance of the island, Mayor Kobayashi seems to do enough to appease the general public. But not everyone. Tracy Walker (Greta Gerwig), a foreign exchange student from Cincinnati, Ohio, immediately calls B.S. on the Mayor’s campaign. In typical American fashion, she worms her way into foreign affairs, launching a schoolwide investigation into Mayor Kobayashi’s administration. She uncovers a conspiracy — a scientist by the name of Professor Watanabe (Akira Ito) has perfected a snout fever serum, which has been silenced by the Mayor.

Back on Trash Island, despite literal and figurative language barriers, the dogs figure out what Atari wants and the majority vote to help him. Except Chief. Chief is not as attached to human relationships as his domesticated allies, but sometimes being the leader means going along with ideas that seem stupid and have a high probability of death. Atari and his new best friends set off on a mission to find Spots, marching across the island and traveling along abandoned tram systems to an emotional musical montage (“I Won’t Hurt You” - The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band). We also discover that Chief is not really against humankind; he is against himself, believing that he is too vicious a dog to be trusted around people. The ragtag pack of reservoir dogs (sorry, bad pun) is later separated by a garbage compactor, leaving Chief alone with the boy. After a game of fetch (seemingly the first in Chief’s life) and a puppy snap biscuit, Chief realizes that he loves the boy who has shown him a simple act of kindness. Atari and Chief hug, surrounded by a literal mountain of trash.

Without revealing any other important plot points, in typical Anderson fashion, I will now list the goals for the characters based on what we know:

Find Spots.

Return Atari to Megasaki.

Eat more puppy snaps.

Cure snout fever.

Repeal oppressive government laws and fight an unjust social system that labels all dogs as mutts and “bad boys.”

Isle of Dogs has all the techniques we’ve come to expect from Wes Anderson: long lists of random items, monologue reading of a written letter, lavish set designs, dioramic cinematography, stilted speech tempo, and omniscient narrators. But when it comes to the actual story, you never know quite what to expect from the quirky director. Anderson’s second stop-motion feature following Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) is a slow-moving, ambling film. It’s hard to find places to go on a small island, but Anderson fills in the spaces with captivating, colorful backgrounds that makes the audience feel like there’s always a spectacle even when not much action is happening. In the musical montage referenced earlier, for example, Atari and the dogs march across various landscapes — a rock bridge over a glittering stream, a broken tram system hovering over cotton-ball clouds and broken industrial pipes — and the unsubtle environmentalist statement is so beautiful, that it’s almost trying to distract you from the fact that the water and air on Trash Island is basically toxic waste and smog.

But that’s the kind of stylish, seemingly contradictory satire for which Anderson has become known. In Isle of Dogs, simple actions have complex consequences; complex concepts are disguised under simple plot arcs. The crux of the film is a very simple idea: a boy wants to be with his dog. That’s it. Atari misses his dog so much that he steals an airplane and travels to an island, facing certain death to do so. It’s a catalyst for a series of consequences back in Megasaki — a public relations nightmare for Mayor Kobayashi in the middle of a re-election campaign, it galvanizes Tracy Walker to stage a protest against the government, and Atari quickly becomes the most exciting event on the news — all of which complicate Atari’s mission. There’s more at stake than simply loving his dog, as most 12-year-old boys do, because while he offers kindness and loyalty to the dogs on the island in the form of puppy snaps, he can’t expect the adults back on Megasaki to offer him the same compassion.

That’s part of the reason that one dot in time — a dog being hugged by a boy, surrounded by a literal mountain of trash — is my personal favorite moment. Atari whispers, “Good boy,” and embraces Chief around his neck. We don’t see Atari’s face, but the camera focuses on Chief. The stray’s periwinkle eyes look down to the right, and then turn to face the audience, staring directly into the camera. His brows raise slightly in surprise; it’s a subtle expression, but one that perfectly shifts the entire relationship for the boy and the dog. This is the first time in Chief’s life he has been shown love, even before being banished to Trash Island. And at first it might seem superficial — a hug, a puppy snap, a game of fetch, and a must needed bath — but in this universe of Anderson’s creation, where everyone is plotting power moves or violently fighting over scraps of food, basic human kindness is often put to the side. It’s almost like a reset button for Chief; he embraces the expression he once detested — “man’s best friend” — showing unwavering loyalty to Atari for the rest of the film.

“Whatever happened to man’s best friend?” is the reoccurring phrase used in Isle of Dogs. So I’m fairly certain it’s the main idea we’re supposed to think about. But it’s a rhetorical question (because no one in the film is willing to provide a concrete answer), and one that viewers might struggle to answer. Probably the biggest fault with Isle of Dogs is that it can feel as though Anderson is trying to lead you to a definitive answer, but doesn’t provide enough clues to formulate an interpretation that feels like it completely fits. Wes Anderson is the kind of director who throws in so much background detail, it’s often hard to tell if it’s a clever metaphor or simply eye candy (or maybe both). So it goes with the characters. Some of the dogs — especially Nutmeg (Scarlett Johansson) — are humorous additions but I struggle to figure out what her role is in the story besides being an instant fascination for doggy romance (though we don’t get any spaghetti and meatballs in this film).

My best surmise is that the answer to “Whatever happened to man’s best friend?” lies within the parallels drawn between humans and dogs. Isle of Dogs loves symbolism and analogies. The dog pack constantly vote on important decisions, mirroring Mayor Kobayashi’s current political campaign. There is exactly one human translator (Frances McDormand), who primarily translates Japanese for English television and radio listeners, and one dog translator named Oracle (Tilda Swinton), who watches television to predict the future for the other dogs. Human-human, dog-dog, and human-dog interactions are practically interchangeable. For example, Megasaki is just a cleaner Trash Island, with Mayor Kobayashi willing to kill (or be killed) in order to establish himself as the top dog. The dogs also concern themselves with human-like interests, such as gossiping about the latest rumors of which dog mated with whom.

It all returns full circle to this idea that simple ideas are disguised under larger concerns. When Anderson asks, “Whatever happened to man’s best friend?”, because of the numerous symbols to parallel humans as dogs and vice versa, the question is essentially wondering whatever happened to basic human decency and kindness, extending to our treatment towards other people, animal, the environment. The moment when Atari and Chief hug is the most pure version of that. They’re refugees, facing certain death and living amongst mountains of rubber tires and glass bottles, but for that one brief dot in time Atari and Chief simply have each other. The boy and his dog are proof that human kindness isn’t dead, but life certainly makes it hard to remember that sometimes.

Isle of Dogs has a lot of themes to unpack, and it’s really quite a heavy film, but it acts as a wonderful introductory film for anyone unfamiliar with Wes Anderson’s work. Dog lovers might be both aghast at the treatment of our beloved pets and extremely emotional by the end, but it’s a film that prioritizes artistic quality over making hardened political stances that could have surfaced from the film. Honestly, I know that I didn’t devote enough time to discuss how Japanese culture plays a crucial role in Isle of Dogs, but I felt like that’s been talked to death enough online among fans. I will say that I feel as though Anderson intentionally set out to makes audience’s feel like their political correctness radar is broken, because Isle of Dogs tiptoes along the line between cultural appropriation and homage. Taiko drummers are an important part of the movie’s score, but all five of the dogs are voiced by middle-aged white men. Even though there’s an American foreign exchange student who feels like she’s intruding on the story (Anderson definitely was doing his own twist on the white savior trope), it’s ironic that she does little to nothing to affect the outcome of the ending. In fact, a beautiful performed haiku does more to change the city of Megasaki than Tracy Walker, which feels like Anderson is trying to subvert certain stereotypes about Americans, but I’m still not 100% sure what that might be.